Read to learn how a shy, timid, weak, and sickly child went to become the most powerful man in the world.

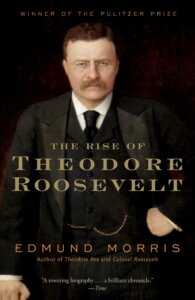

How can a book capture a man who is larger than life? You can write thousands of pages and there will be something missing. But The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt by Edmund Morris comes as close as possible to such an epic undertaking.

I don’t give this book 5 stars because it covered America’s inner political workings in too much detail while dedicating less to more interesting episodes such as the war in Cuba and Theodore’s life after he became President.

I am rambling now. But you cannot write about Theodore Roosevelt without rambling. His life was far from a straight line into political glory. It was all curves and detours, which is what makes him so interesting. Besides being President he was the author of thirty-eight books, natural historian, boxer, hunter, book nerd, war hero, police reformer, governor, cowboy, sheriff, farmer. From shy, asthma-ridden “Teedie” to “President Theodore Roosevelt” — the man who led America into its most glorious century.

His contradictory personality made him feel at ease anywhere. He felt as comfortable in upper-crust luncheons as spending days in the wild chasing bandits.

“At dawn Roosevelt woke to the hoarse clucking of hundreds of prairie-fowl. Sallying forth with his rifle, he shot five sharptails. “It was not long before two of the birds, plucked and cleaned, were split open and roasted before the fire. And to me they seemed like the most delicious food.” Exactly one month before he had been campaigning on the platform of Chickering Hall in New York, twisting his eyeglasses, catching bouquets, and blushing under the admiring gaze of bejeweled society matrons.”

I can see why modern palates would find him distasteful. He was a stubborn expansionist. But Roosevelt can vindicate himself even in this questionable pursuit. Unlike contemporary politicians, he was the first one to ride into the war he so fiercely encouraged.

He was also one of the first major politicians who campaigned against Jewish persecution, believed in equal opportunities regardless of color, and “remained acutely aware of the needs and sensibilities of women”.

But men greater than life share the same woes as everyone else. He has insecurities like everyone else. He confessed to his closest confidants that he thought his career in politics was over before even becoming governor.

“I have not believed and do not believe that I shall ever be likely to come back into political life.”

Despite descending from an affluent family he had money problems and severe doubts as to “what the future holds for him”.

“I am afraid it is too big a task for me [writing a book]. I wonder if I won’t find everything in life too big for my abilities.”

His intense physical regimen philosophy laid out America’s obsession with fitness and muscularity more than half a century before Arnold Schwarzenegger stepped foot in the country. Millions emulated his “strenuous life” and voluntarily sought physical discomfort for self-improvement.

Theodore Roosevelt was more than a President. And The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt by Edmund Morris lays him out better than any other book.

Key takeaways

- Action is at the core of self-actualization.

- You can bend life to your own will.

- Voluntary discomfort will improve your life.

Memorable passages from The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt

“It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.”

“A just war is in the long run far better for a man’s soul than the most prosperous peace.”

“Theodore [Theodore Sr] said, eschewing boyish nicknames, “you have the mind but you have not the body, and without the help of the body the mind cannot go as far as it should. You must make your body. It is hard drudgery to make one’s body, but I know you will do it.”

“On winter evenings . . . strollers may observe the President (Theodore) wading pale and naked into the ice-clogged stream, followed by shivering members of his Cabinet.”

“Roosevelt has spent many thousands of hours punishing a variety of steel springs and gymnastic equipment, yet his is not the decorative brawn of a mere bodybuilder. Professional boxers testify that the President is a born fighter who repays their blows with interest.”

“It is not often that a man can make opportunities for himself. But he can put himself in such shape that when or if the opportunities come he is ready to take advantage of them.”

“If he senses any sexual interest in him, Theodore Roosevelt shows no sign: in matters of morality he is as prudish as a dowager. That small hard hand has caressed only two women.”

“Roosevelt will take advantage of the holiday quietness of his dark-green office to do some writing. Besides being President, he is also a professional author.”

“The President manages to get through at least one book a day even when he is busy.”

“Somewhere between six one evening and eight-thirty next morning . . . he had read a volume of three-hundred-and-odd pages, and missed nothing of significance that it contained.”

“On evenings like this, when he has no official entertaining to do, Roosevelt will read two or three books entire.”

“Reading for him is the purest imaginative therapy.”

“[About his father] He took an exuberant, masculine joy in life . . . exercising with the energy of a teenager, waltzing all night in society balls.”

“Theodore . . . acquired a love for legend and anecdote, and inherited a nostalgia for a way of life he had never known . . . As a adult reader of history, and as a writer of it, he always shoed a tendency to “live” his subject: he always looked for narrative which as instinct tells the truth that both charms and teaches.”

“Having been a sickly boy, with no natural bodily prowess, and having lived much at home, I was at first quite unable to hold my own when thrown into contact with other boys of rougher antecedents. I was nervous and timid. Yet from reading of the people I admired—ranging from the soldiers of Valley Forge, and Morgan’s riflemen, to the heroes of my favorite stories—and from hearing of the feats performed by my Southern forefathers and kinsfolk, and from knowing my father, I felt a great admiration for men who were fearless and who could hold their own in the world, and I had a great desire to be like them.”

“Accordingly, with my father’s hearty approval, I started to learn to box. I was a painfully slow and awkward pupil, and certainly worked two or three years before I made any perceptible improvement whatever.”

” . . . He remained aloof from the deck-games of other children on board, burying himself in books.”

“Teedie pushed and pulled and stretched and swung, working himself into the rhythmic trance of the true body-builder. For Teedie the work was both release and pleasure. He exercised throughout . . . fiber by fiber, his muscles tautened, while the skinny chest expanded by degrees perceptible only to himself. But his overall results were dramatic… glorifying in his newfound strength, he plunged into the depths of icy rapids, and chambers to the height of seven mountains.”

“A friend of the period remembered him as the most studious little brute I ever knew in my life.”

“The humiliation [he was bullied] forced him to realize that his two years of bodybuilding had achieved only token results . . . by the harsh standards of the world he was still a weakling. There and then he decided to join what he described as “the fellowship of the doers”. If he had exercised hard before, he must do so twice as hard now. He must also learn how to give and take punishment . . . I started to learn to box.”

“No doubt [his fathers] businessman’s eye had already discerned that his absentminded and unorthodox youth would be a disaster in the world of commerce.”

“. . . noted that bribery alone gained access to the birth-place of Christ . . .”

“He was now, if not yet a man, then at least a youth of more than ordinary experience of the world. He had traveled exhaustively in Britain, Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East . . . He had plumbed the Catacombs and climbed the Great Pyramid, slept in a monastery and toured a harem. He had hunted jackals on horseback, kissed the Pope’s hand, stared into a volcano, traced an ancient civilization to its source, and followed the wanderings of Jesus.”

“. . . he carefully researched the “antecedents” of potential friends . . . “

“. . . . he could analyze lightweight boxing techniques, discuss the aerodynamics of birds and the protective coloration of animals, quote at will from the Nibelungenlied and the speeches of Abraham Lincolhn, and explain what it was like trying to remain submerged in the Dead Sea. He was “queer”, he was “crazy”, he was a “bundle of eccentricities”, but he was wholly interesting.”

“In addition to boxing, wrestling, body-building, and his daily hours of recitation, the young freshman attended weekly dancing-classes, hunted in the woods, taught in Sunday stuffed and dissected his specimens, organized a whist club, took part in poetry-reading sessions.”

“Sickly and reclusive as a child, preoccupied with travel and self-improvement in his teens, he had little opportunity to knock on strange doors . . .”

“Nether during his student years, nor indeed at any time in his life, did Theodore show tolerance for women [or for that matter men] who were anything but “rigidly virtuous.” His judgements of people lower down the moral or social scale could be particularly prudish . . . Sex, to him, was part of the mystical union of marriage, and, however pleasurable as an act of love, its function was to proceate. Outside marriage it simply did ot exist”.

“. . . he developed into something of a fashion plate, or as he described himself, “very swell”.

“Iron self-discipline had become a habit with him . . . the amount of time he spent at his desk was comparatively small — rarely more than a quarter of the day — but his concentration was so intense, and his reading so rapid, that he could afford more time off than most. Even these free periods were packed with mental, physical, or social activity . . . never have I seen or read of a man with such an amazing array of interests. Tumbling into bed at midnight or in the small hours, Theodore could luxuriate in healthy tiredness, satisfied that he had wasted not one minute of his waking hours. His regimen was flexible, but balanced. Any overindulgence in sport or flirtation would be immediately compensated for by extra study.”

“If I was not going to earn money, I must even things up by not spending it . . . if I went into a scientific career, I must definitely abandon all thought of the enjoyment that could accompany a money-making career, and must find my pleasures elsewhere.”

“He continued faithfully to exercise and teach in Sunday school, obedient to a precept of his fathers which he had never forgotten: “Take care of your morals first, your health net, and finally your studies.”

“I do not think I ever remember him being “out of sorts.” He did not feel well sometimes, but he never would admit it.”

“Being headstrong and aggressive, on occasion, is a pretty good thing.”

“Ho are the nobles of the earth,

The true aristocrats,

Who need not bow their heads to lords,

Nor deff to kings their hats?

Who are they but the men of toil,

The mighty and the free,

Whose hearts and hands subdue the earth,

And compass all the sea?

Who are they but the men of toil.”

“Theodore could sense the waves of peace and security which flow around the enclaves of the very rich.”

“Wine makes me awfully fighty. A hangover confirmed his lifelong resolve never to get drunk again, and the evidence is he never did.”

” . . . he vowed, with all the strength of his passionate nature, that he would marry her.”

“O being called to speak he seemed very shy and made, what I think he said, was his maiden speech. He still had difficulty enunciating clearly or even in running off his words smoothly . . . but still it is interesting to me to recall that this was the beginning of the public speaking of the man who later addressed more audiences than any other orator in his time and made a deeper impression by his spoken word.”

“The reason he knew so much about everything was that wherever he went he got right in with the people.”

“He never recorded what was ominous, unresolved, or disgraceful. Triumph was worth the ink: tragedy was not.”

“[Bram Stoker] wrote in his diary: “Must be President some day. A man you can’t cajole, can’t frighten, can’t buy.”

“They spent ten hours a day up to their hips in icy water, stumbling constantly on sharp, slimy stones. . .”

“If still not altogether certain about his career, he at least knew roughly what he would like to do . . . For once, he could look back in the past without regret, and at the future without bewilderment.”

“Alice’s resistance to his advances . . . began to show signs of permanent hardening. Theodore plunged into a state of sleepless frustration. “Oh the changeableness of the female mind! . . . “I did not think I could win her,” he confessed, “and I went nearly crazy at the mere thought of losing her.”

“See that girl?” he exclaimed, pointing across the room at Alice: “I am going to marry her. She won’t have me, but I am going to have her. . . Theodore felt the loneliness of unrequited love weigh heavily upon him . . . so he began to write a book.”

“I have been in love with her for two years now; and have made everything subordinate to winning her…”

“Roosevelt seemed constantly afraid,” recalled Alice’s cousin, “that someone would run off with her . . .”

“He already made it clear that he considered [studying law] a stepping-stone to politics . . .”

“I do not think a woman should assume the man’s name … I would have the world “obey” used not more by the wife than the husband.”

“. . . he would remain acutely aware of the needs and sensibilities of women. Few things disgusted him more than “male sexual viciousness” . . . “

“Doctor” I’m going to do all the things you tell me not to do. If I’ve got to live the sort of life you have described, I don’t care how short it is.”

“. . . the domestic routine which he would always consider the height of human bliss.”

“. . . in the end I found out that we each have to work in his own way to do our best . . .”

“He was predestined to politics…he could not escape the fate of being persistently in the public eye.”

“It is often that a man can make opportunities for himself. But he can put himself in such shape that when or if the opportunities came he is ready to take advantage of them.”

“. . . . I acknowledge no man as my superior, except for his own worth, or as my inferior, except for his own demerit.”

“Theodore himself reveled in “the excitement and perpetual conflict” of politics, the feeling that he was “really being of some use in the world.”

“…. he adhered to the classic credo that every citizen is master of his fate.”

“… Two years before, Grover Cleveland had been an obscure upstate lawyer, fortyish, unmarried, Democratic, remarkable only for his ability to work thirty-six hours at a stretch without fatigue.”

“By modern standards, these spells of wild abandon were laughably sedate; Roosevelts disdain for “low drinking and dancing saloons” was marked even in 1883.”

“The difference between yoru party and ours, is that your bad men throw out the good ones, while with us the good throw out the bad.”

“The wealthy criminal class…”

“…and here in God’s country, freedom beckoned them both.”

“Roosevelt was not by nature a businessman. His tendency to spend freely, and invest in dubious schemes on impulse, had long been a source of alarm to the more responsible members of his family. . .”

“He threw himself with zest back into legislative business, working up to fourteen hours a day. Every morning, to speed up his metabolism, he indulged in half an hour’s fierce sparring with a young prizefighter in his rooms. “I feel much more at ease in my mind and better able to enjoy things since we have gotten under way.”

“The pain in his heart might be dulled by sheer fatigue.”

“Roosevelt was nervy, inspirational, passionate. He arrived at conclusions so rapidly that he seemed to be acting wholly on impulse, and was impatient when those with more laborious minds did not instantly agree with him. Cleveland, on the other hand, was slow, stolid, objective, almost maddeningly conscientious. No bill was too lengthy, or too complex, for him to scrutinize it down to the last punctuation-mark.”

“I have very little expectation of being able to keep on in politics; my success so far has only been won by absolute indifference to my future career.”

“. . . A boyhood ambition is rising within him. He will take a rifle, load up a horse, and ride off into the prairie, absolutely alone, for days and days—“far off from all mankind.”

“One cannot read his descriptions of the trip without sensing his overwhelming delight in being free at last. “Black care,” Roosevelt wrote, “rarely sits behind a rider whose pace is fast enough.”

“He subtly sounded a favorite theme: that of the masculine hardness of the practical politician, as opposed to the effeminate softness of armchair idealists.”

“The slow, exasperating drawl and the unique accent that the New Yorker feels he must use when visiting a less blessed portion of civilization had disappeared, and in their place is a nervous, energetic manner of talking with the flat accent of the West.” In New York, another reporter was struck by his “sturdy walk and firm bearing.”. . “He was now, in the words of Bill Sewall, “as husky as almost any man I have ever seen who wasn’t dependent on his arms for his livelihood.”

“Roosevelt allowed himself eight idyllic weeks in the East during the summer of 1885—his first period of relaxation in two years.”

“Roosevelt . . . proceeded to devour Anna Karenina, in between spells of guard duty. He saw nothing incongruous in this. “My surroundings were quite grey enough to harmonize with Tolstoy.” The book both attracted and repelled him. His subsequent review of it for Corinne reveals a strange combination of sophistication and naiveté in his critical intellect, plus the insistence that all art should reaffirm certain basic moral values.”

“When young Senator Benton emerges as the spokesman for these people, the parallels between his own and Roosevelt’s character grow clear. They are both politicians born to articulate the longings of the inarticulate. . .”

“Here we are not ruled over by others, as is the case in Europe; here we rule ourselves.…”

“Roosevelt conceded that “some of the evils of which you complain are real and can be to a certain degree remedied, but not by the remedies you propose.” But most would disappear if there were more of “that capacity for steady, individual self-help which is the glory of every true American.” Legislation could no more do away with them “than you could do away with the bruises which you receive when you tumble down, by passing an act to repeal the laws of gravitation.”

“This third political defeat in just over two years became one of those memories which he ever afterward found too painful to dwell on.”

“Not only was this American cultured, talkative, and well-connected, he had a certain raw physical force, and a sense of personal direction (for all his recent rejection at the polls) that transcended Spring Rice’s own petty ambitions at the Foreign Office. Although Roosevelt was only four months older, he seemed to have lived at least a decade longer.”

“Although his Dakota venture had impoverished him, he was nevertheless rich in nonmonetary dividends. He had gone West sickly, foppish, and racked with personal despair; during his time there he had built a massive body, repaired his soul, and learned to live on equal terms with men poorer and rougher than himself. He had broken horses with Hashknife Simpson.”

“The message was clear: he must once again forget about politics and seek success in literature. For the foreseeable future, he would have to earn a living with his pen.”

“. . . you are not the timber of which Presidents are made.”

“As always, he found it difficult to marshal his superabundant thoughts on paper. A perusal of the manuscript of Volume One shows what agonies its magnificent opening chapter, “The Spread of the English-Speaking Peoples,” cost him. A veritable thicket of verbal debris—interlineations, erasures, blots, and balloons—clogs every page: only the clearest prose is allowed to filter through. “

“Oh Lord, help me kill that b’ar, and if you don’t help me, oh Lord, don’t help the b’ar.”

“What was worse, for the first time he felt really insecure in his job.”

“Ill-born but well-married, John Hay was a spectacularly fortunate man.”

“Roosevelt had “that singular primitive quality that belongs to ultimate matter—the quality that medieval theology assigned to God—he was pure act. ”

“Roosevelt flipped the book shut a changed man…”

“Twenty miles of country road, and a yawning social gulf, separated their respective Long Island establishments. At Sagamore Hill the talk was of books and public affairs; at Hempstead, of parties, fashions, and horseflesh. On the rare occasions when the brothers met, friends were struck by the reversal of their teenage roles: where once Theodore had been sickly and solitary, and Elliott [his brother] an effulgent Apollo, now it was the elder who glowed, and the younger who was wasting away.”

“Alcoholism he believed to be a disease that could be treated and cured. But infidelity was a crime, pure and simple; it could be neither forgiven nor understood, save as an act of madness. It was an offense against order, decency, against civilization; it was a desecration of the holy marriage-bed. By reducing himself to the level of a “flagrant man-swine,” Elliott had forfeited all claim to his wife and children.”

“Force rules the world still,

Has ruled it, shall rule it;

Meekness is weakness,

Strength is triumphant!”

“He [Roosevelt] admires individual achievement above all things.”

“To all who have known really happy family lives,” he writes, “that is, to all who have known or who have witnessed the greatest happiness which there can be on this earth, it is hardly necessary to say that the highest idea of the family is attainable only where the father and mother stand to each other as lovers and friends. In these homes the children are bound to father and mother by ties of love, respect, and obedience, which are simply strengthened by the fact that they are treated as reasonable beings with rights of their own, and that the rule of the household is changed to suit the changing years, as childhood passes into manhood and womanhood.”

“Roosevelt is making no effort to be metaphorical, but this whole simple and beautiful passage may be taken as symbolic of his attitude to his country and the world. Father is Strength in the home, just as Government is Strength in America, and America is (or ought to be) Strength overseas. Mother represents Upbringing, Education, the Spread of Civilization. Children are the Lower Classes, the Lower Races, to be brought to maturity and then set free.”

“. . .but Roosevelt knew he would still have to scrabble for freelance pennies during the next few years in order to save his home and educate his children.”

“Never, never, you must never either of you remind a man at work on a political job that he may be President. It almost always kills him politically. He loses his nerve; he can’t do his work; he gives up the very traits that are making him a possibility. I, for instance, I am going to do great things here, hard things that require all the courage, ability, work that I am capable of … But if I get to thinking of what it might lead to—”

“Life is strife . . . There is an unhappy tendency among certain of our cultivated people,” Roosevelt went on, “to lose the great manly virtues, the power to strive and fight and conquer.”

“Roosevelt, like Hanna, began to feel pangs of real dread. He was “appalled” at Bryan’s ability “to inflame with bitter rancor towards the well-off those … who, whether through misfortune or through misconduct, have failed in life.”

“No triumph of peace is quite so great as the supreme triumphs of war.”

“All the great masterful races have been fighting races; and the minute that a race loses the hard fighting virtues, then … it has lost its proud right to stand as the equal of the best.”

“Cowardice in a race, as in an individual,” he declared, “is the unpardonable sin.”

“Better a thousand times err on the side of over-readiness to fight, than to err on the side of tame submission to injury, or cold-blooded indifference to the misery of the oppressed.”

“There are higher things in this life than the soft and easy enjoyment of material comfort. It is through strife, or the readiness for strife, that a nation must win greatness. We ask for a great navy, partly because we feel that no national life is worth having if the nation is not willing, when the need shall arise, to stake everything on the supreme arbitrament of war, and to pour out its blood, its treasure, and its tears like water, rather than submit to the loss of honor and renown.”

“And nothing could be more satisfying than to see his own progeny growing sturdy and sunburned in his own fields. Roosevelt confessed to Cecil Spring Rice that “the diminishing rate of increase” in America’s population worried him in contrast to the fecundity of the Slav. Looking around Sagamore Hill, he gave thanks that his own family, at least, had shown valor in “the warfare of the cradle.”

“Theodore Roosevelt … was pure act.”

“Long did not understand that extreme crisis, whether of an intimate or public nature, had precisely the reverse effect on Theodore Roosevelt. The man’s personality was cyclonic, in that he tended to become unstable in times of low pressure. The slightest rise in the barometer outside, and his turbulence smoothed into a whirl of coordinated activity, while a core of stillness developed within. “

“I know perfectly well that one is never able to analyze with entire accuracy all of one’s motives,” he wrote in a formal reply to the Sun. “But … I have always intended to act up to my preachings if occasion arose. Now the occasion has arisen, and I ought to meet it.”

“But the most eagerly awaited refreshments were free watermelons and jugs of iced beer at stopping-places en route. These were passed through the car windows by “girls in straw hats and freshly starched dresses of many colors,” whose beauty some troopers would remember for half a century.”

“According to at least two accounts, Roosevelt was nevertheless so depressed about the tax scandal that he went to Platt and suggested that he withdraw his candidacy. “Is the hero of San Juan Hill a coward?” sneered the old man. “By Gad! I’ll run.”

“I have played it with bull luck this summer,” he wrote Cecil Spring Rice. “First, to get into the war; then to get out of it; then to get elected. I have worked hard all my life, and have never been particularly lucky, but this summer I was lucky, and I am enjoying it to the full. I know perfectly well that the luck will not continue, and it is not necessary that it should. I am more than contented to be Governor of New York, and shall not care if I never hold another office.”

“I have always been fond of the West African proverb: ‘Speak softly and carry a big stick; you will go far.”

“Here was no soft, hesitant wooer, she felt, “but one who would come at once to the question, and, if the lady repulsed him, bear her away despite herself, as some of his ancestors must have done in the pliocene age.”

“. . . he traveled farther and spoke more than any candidate, presidential or vicepresidential, in nineteenth-century history, with the exception of Bryan himself, four years before.”

The following timetable of one undated campaign day survives from the diary of an aide:

7:00 A.M. Breakfast

7:30 A.M. A speech

8:00 A.M. Reading a historical work

9:00 A.M. A speech

10:00 A.M. Dictating letters

11:00 A.M. Discussing Montana mines

11:30 A.M. A speech

12:00 Reading an ornithological work

12:30 P.M. A speech

1:00 P.M. Lunch

1:30 P.M. A speech

2:30 P.M. Reading Sir Walter Scott

3:00 P.M. Answering telegrams

3:45 P.M. A speech

4:00 P.M. Meeting the press

4:30 P.M. Reading

5:00 P.M. A speech

6:00 P.M. Reading

7:00 P.M. Supper

8–10 P.M. Speaking

11:00 P.M. Reading alone in his car

12:00 To bed.”

Write a Comment