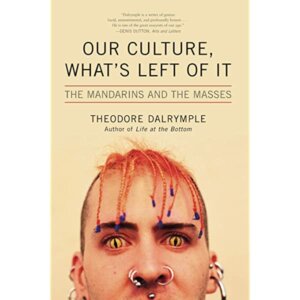

Our Culture, What’s Left of It poses a controversial question. What if liberal policies are harming us?

Theodore Dalrymple is the psychiatrist of the British underclass. After spending years treating drug addicts, convicts, victims, and perpetrators of abuse he concluded that the main cause of their behavior is culture.

The idea that people should be freed from social convention and self-control, aided by the welfare state has created massive social problems in Britain and other developed countries.

A poor culture leads to poor behavior; which trickles down to policies, parents, and finally to children, where the cycle repeats itself.

He critiques the “ugliness of our modern culture” and how its wide acceptance has impoverished the arts, literature, cities, relationships, families, and our mental being.

Some examples.

Sexual liberation increased unfaithfulness, which lowered trust among couples, which leads to possessive jealousy and domestic violence.

Families not meeting together for dinner every evening leads to bad eating habits, which deteriorate our bodies, souls, and minds.

Today, ugliness is peddled like newspapers as soon as a war breaks out. Music videos in the 70s and 80s had vitality, they provoked positive emotion. Today’s stuff is dark, oversexualized, vulgar and lacks positive emotions.

Twerking for example. In what dimension can it be considered sexy, entertaining, or worthwhile? You have women in their prime of beauty and vigor denigrating themselves just because the dance became culturally accepted.

“Art” is whatever the artist wants it to be. Splash period blood on a canvas, attach it with a progressive talking point, and you are considered an artist. The bar is set that low. There are talented and skillful artists out there who are not getting the credit they deserve while modern art is shoved in our faces as “enlightened”.

If it’s freakish, it’s “culture”. If it triggers an emotion (even if it’s gag reflex) it’s art. If it’s different, original, foreign, it must be accepted by default. If it feels good you should “go for it”. If you mess up, it’s not your responsibility. Live how you want to live, then when the world comes crashing down on you, book a session with your therapist and it will all be fine.

With Our Culture, What’s Left of It, Theodore Darlympile sheds light on the negatives of the liberal ideas which the west has accepted as indisputable. But what if the way of life championed by these ideas is deeply flawed?

Memorable passages from Our Culture, What’s Left of It

“A crude culture means a coarse people”.

“Almost every intellectual claims to have the welfare of humanity, and particularly the welfare of the poor, at heart: but since no mass murder takes place without its perpetrators alleging that they are acting for the good of mankind, philanthropic sentiment can plainly take a multiplicity of forms.”

“Medically speaking, the poor are more interesting, at least to me, than the rich: their pathology is more florid, their need for attention greater. Their dilemmas, if cruder, seem to me more compelling, nearer to the fundamentals of human existence.”

“Intellectuals propounded the idea that man should be freed from the shackles of social convention and self-control, and the government, without any demand from below, enacted laws that promoted unrestrained behaviour and created a welfare system that protected people from some of its economic consequences.”

“There is something to be said here about the word ‘depression,’ which has almost entirely eliminated the word and even the concept of unhappiness from modern life. Of the thousands of patients I have seen, only two or three have ever claimed to be unhappy: all the rest have said that they were depressed. This semantic shift is deeply significant, for it implies that dissatisfaction with life is itself pathological, a medical condition, which it is the responsibility of the doctor to alleviate by medical means. Everyone has a right to health; depression is unhealthy; therefore everyone has a right to be happy (the opposite of being depressed). This idea in turn implies that one’s state of mind, or one’s mood, is or should be independent of the way that one lives one’s life, a belief that must deprive human existence of all meaning, radically disconnecting reward from conduct. A ridiculous pas de deux between doctor and patient ensues: the patient pretends to be ill, and the doctor pretends to cure him. In the process, the patient is wilfully blinded to the conduct that inevitably causes his misery in the first place.

“This truly is not so much the banality as the frivolity of evil: the elevation of passing pleasure for oneself over the long-term misery of others to whom one owes a duty. What better phrase than the frivolity of evil describes the conduct of a mother who turns her own 14-year-old child out of doors because her latest boyfriend does not want him or her in the house?”

“There has been a long march not only through the institutions but through the minds of the young. When young people want to praise themselves, they describe themselves as ‘nonjudgmental.’ For them, the highest form of morality is amorality.”

“The consequences to the children and to society do not enter into the matter: for in any case it is the function of the state to ameliorate by redistributive taxation the material effects of individual irresponsibility, and to ameliorate the emotional, educational, and spiritual effects by an army of social workers, psychologists, educators, counsellors, and the like, who have themselves come to form a powerful vested interest of dependence on the government”

“My only cause for optimism during the past 14 years has been the fact that my patients, with a few exceptions, can be brought to see the truth of what I say: that they are not depressed; they are unhappy—and they are unhappy because they have chosen to live in a way that they ought not to live, and in which it is impossible to be happy.”

“The existence of malnutrition in the midst of plenty has not entirely escaped either the intelligentsia or the government, which of course is proposing measures to combat it: but, as usual, neither pols nor pundits wish to look the problem in the face or make the obvious connections. For them, the real and most pressing question raised by any social problem is: ‘How do I appear concerned and compassionate to all my friends, colleagues, and peers?’ Needless to say, the first imperative is to avoid any hint of blaming the victim by examining the bad choices that he makes. It is not even permissible to look at the reasons for those choices, since by definition victims are victims and therefore not responsible for their acts, unlike the relatively small class of human beings who are not victims.”

“One man’s poverty is another man’s employment opportunity: as long ago as the sixteenth century, a German bishop remarked that the poor are a gold mine”

“While the Indian store gives the impression of intense activity and hope, the convenience store in a white working-class area gives the impression of passivity and despair.”

“The second is to avoid all appearance of blaming people whose lives are poor and unenviable. That this approach leads it to view those same people as helpless automata, in the grip of forces that they cannot influence, let alone control—and therefore as not full members of the human race—does not worry the intelligentsia in the least”

“There are few exhilarations greater than being completely beyond the reach of anyone who might help you—provided of course that the dangerous situation has been freely chosen and not imposed and that there is somewhere safe to return to when the excitement has either worn off or become overwhelming. Not surprisingly, I have found my frequent returns to the workaday world of mortgages, regular hours, and supermarket shopping less than wholly pleasurable”

“Untold numbers of my patients, with every opportunity to lead quiet, useful, and tolerably prosperous lives, choose instead the path of complication and, if not of violence and physical danger exactly, at least of drama and excitement, leading to sleepless nights and financial loss. They break up marriages, form disastrous liaisons, chase Chimeras, and behave in ways that predictably will end in disaster. Like moths to the flame, they court catastrophe. As many have told me, they prefer disaster to boredom.”

“Those who are not satisfied with their work, or who have no intellectual or cultural interests, and whose coarse emotions have undergone refinement neither by education nor by adherence to civilised custom, are particularly liable to seek out the compensatory complications of domestic disorder and disarray. The perpetually unemployed, for example, lead a crude and frequently violent version of the life portrayed in Les Liaisons Dangereuses. Like French aristocrats under the ancien regime, they are—thanks to Social Security—under no compulsion to earn a living; and with time hanging heavy on their hands, their personal relationships are their only diversion. These relationships are therefore both intense and shallow, for there is never any mutual interest in them deeper than the avoidance of the ever-encroaching ennui.

“Just as the man who fights iniquity is seldom wholly satisfied by its defeat (for what is there for him to do thereafter?)”

“I learned early in my life that, if people are offered the opportunity of tranquillity, they often reject it and choose torment instead”

“For a long time I pitied myself: had any child ever been as miserable as I? I felt the deepest, most sincere compassion for myself. Then gradually it began to dawn on me that the education I had received had liberated me from any need or excuse to repeat the sordid triviality of my parents’ personal lives. One’s past is not one’s destiny, and it is self-serving to pretend that it is. If henceforth I were miserable, it would be my own fault: and I vowed never to waste my substance on petty domestic conflict.”

“The only thing worse than having a family, I discovered, is not having a family. My rejection of bourgeois virtues as mean-spirited and antithetical to real human development could not long survive contact with situations in which those virtues were entirely absent; and a rejection of everything associated with one’s childhood is not so much an escape from that childhood as an imprisonment by it.”

“Until then, I had assumed, along with most of my generation unacquainted with real hardship, that a scruffy appearance was a sign of spiritual election, representing a rejection of the superficiality and materialism of bourgeois life. Ever since then, however, I have not been able to witness the voluntary adoption of torn, worn out, and tattered clothes—at least in public—by those in a position to dress otherwise without a feeling of deep disgust. Far from being a sign of solidarity with the poor, it is a perverse mockery of them…”

“The comment of an Italian stood out like a beacon of truth in this murk of dishonesty: ‘É molto emocionante. Se non fosse la guerra, che cosa farebbero i reporter?’ Very moving. If it weren’t for war, what would journalists do?”

“The need to always lie and always to avoid the truth stripped everyone of what Custine called ‘the two greatest gifts of God—the soul and the speech which communicates it.’ People became hypocritical, cunning, mistrustful, cynical, silent, cruel, and indifferent to the fate of others as a result of the destruction of their own souls. Moreover, the upkeep of systematic untruth requires a network of spies: indeed, it requires that everyone become a spy and potential informer. And ‘the spy,’ wrote Custine, ‘believes only in espionage, and if you escape his snares he believes that he is about to fall into yours.’ The damage to personal relations was incalculable.

“If Custine were among us now, he would recognise the evil of political correctness at once, because of the violence that it does to people’s souls by forcing them to say or imply what they do not believe but must not question. Custine would demonstrate to us that, without an external despot to explain our pusillanimity, we have willingly adopted the mental habits of people who live under a totalitarian dictatorship.”

“Tocqueville observed the voluntary idleness to which the seemingly humane system of entitlement gave rise—how it destroyed both kindness and gratitude (for what is given bureaucratically is received with resentment), how it encouraged fraud and dissimulation of various kinds, and above all how it dissolved the social bonds that protected people from the worst effects of poverty.

“Admittedly, corruption is a strange kind of virtue: but so is honesty in pursuit of useless or harmful ends. Corruption is generally held to be a vice, and viewed in the abstract, it is. But bad behaviour can sometimes have good effects, and good behaviour bad effects.”

“Where the state looms large in everyone’s life, a degree of corruption exerts a beneficial effect upon the character of the people.”

“Italian municipalities have also kept their cities vibrant by capping the local taxes of small businesses, thus nurturing a variety of shops that in turn nourish many crafts, from papermaking to glass-blowing, that might otherwise have died. Thus, an uneducated man in Italy can still be a proud craftsman, while in Britain he must take a low-paid, unskilled job—if he takes a job at all. Italian downtowns are not as British city centres are, the location of depressingly uniform chain stores without character or individuality, plate-glassed emporia hacked into the ground floors of historic buildings without regard to the original architecture. The Italians have solved, as the British have not, the problem of living in a modern way in ancient surroundings that, looked at in economic terms, constitute inherited wealth.”

“What is the point of wiping a table, if the world around it is irredeemably hideous? To be sure, self-respect can encourage people to make the best of a bad job, but dependency on the state has destroyed the basis of self-respect.”

“An uncorrupt leviathan state is, in fact, more to be feared than a corrupt one. Indeed, if the Italian state were to turn honest without a simultaneous reduction in its size, the result would be an economic and cultural catastrophe for Italy.”

“Yet the prescription of the drug (Prozac) (and others like it) to millions of people has not noticeably reduced the sum total of human misery or the perplexity of life. A golden age of felicity has not arrived: and the promise of a pill for every ill remains, as it always will, unfulfilled.”

“Macbeth, however, is not a resentful man; he never complains of ill-treatment. So while resentment is a cause of man’s evil, it is not the sole or fundamental cause. Macbeth is led to evil by his ambition: and because we all live in society, in which jockeying for position and power is inevitable, we all understand him from within. Macbeth is us without the moral scruples.”

“The tool that Lady Macbeth uses to galvanise her husband into action is humiliation. She humiliates him into doing what he knows to be wrong, just as many of my patients who take heroin started to take it because they were afraid to seem weak in the eyes of their associates. Macbeth loves and respects his wife, but Lady Macbeth perverts his love—and his essential, ineradicable, and often laudable human desire to be respected and loved by the person one respects and loves—to the purposes of evil. The lesson is that any powerful emotion or desire, however virtuous in many circumstances, can be turned to evil purposes if it escapes ethical control.”

“Macbeth warns us to preserve our humanity by accepting limitations to our actions. As Macduff says to Malcolm, when the latter presents himself as a heartless libertine:

Boundless intemperance

“In nature is a tyranny.

Only if we obey rules—the rules that count—can we be free.”

“I do not think, for example, that Shakespeare would view the sexual free-for-all of contemporary Britain—with its harvest of child neglect and abuse, morbid jealousy, sexual violence, and egocentric savagery—with the complacent impassivity of today’s British intelligentsia. On the contrary: he would loathe it, for its consequences are precisely what he sees lurking in human nature if civilising restraint be removed.

“But this response shows a lack of historical understanding and imagination. Throughout most of history, chastity has been honoured as an important virtue, precisely because it helps to control and civilise sexual relations. It has often been horribly overvalued, of course: for example, only last week a Kurdish Muslim refugee in Britain cut his own 16-year-old daughter’s throat and left her to bleed to death because she was dressing in revealing western clothes and having sex with her boyfriend. But Isabella knows that a society that places no value at all on chastity will not place much value on fidelity either: and then we are back to the free-for-all and all its attendant problems. She fears not only for her own soul if she sins, but for that of society.”

“The key word is ‘beastly’: their beastly touches. By beastliness, the Duke means sexuality without the human qualities of love and commitment: for without love, sex is merely animal—beastly in the most literal sense.”

“In 1914, for example, Bernard Shaw caused a sensation by giving Eliza Doolittle the words ‘Not bloody likely!’ to utter on the London stage. Of course, the sensation that this now-innocuous, even innocent exclamation created depended wholly for its effect upon the convention that it flouted: but those who were outraged by it (and who have generally been regarded as ridiculous in subsequent accounts of the incident) instinctively understood that sensation doesn’t strike in the same place twice, and that anyone wanting to create an equivalent in the future would have to go far beyond ‘Not bloody likely.’ A logic and a convention of convention-breaking was established, so that within a few decades it was difficult to produce any sensation at all except by the most extreme means.

“In the realm of personal morality, Zweig appealed for subtlety and sympathy rather than for the unbending application of simple moral rules. He recognised the claims both of social convention and of personal inclination, and no man better evoked the power of passion to overwhelm the scruples of even the most highly principled person. In other words, he accepted the religious view (without himself being religious) that Man is a fallen creature, who cannot perfect himself but ought to try to do so.”

“Zweig implies that only the reticent and self-controlled can feel genuine passion and emotion. The nearer emotional life approaches to hysteria, to continual outward show, the less genuine it becomes. Feeling becomes equated with vehemence of expression, so that insincerity becomes permanent. Zweig would have dismissed our modern emotional incontinence as a sign not of honesty but of an increasing inability or unwillingness truly to feel.”

“Not only does sex education start earlier and earlier in our schools, but publications, films, and television programs for ever-younger age groups grow more and more eroticised. It used to be that guilt would accompany the first sexual experiences of young people; now shame accompanies the lack of such experiences.”

“Those who live lives of immediate gratification, Huxley thought, would not be able to bear solitude of any kind. As Mustapha Mond explains, ‘people are never alone now. We make them hate solitude; and we arrange their lives so that it’s almost impossible for them to ever have it.’ A life devoted to instant gratification produces permanent infantilisation: ‘at sixty-four . . . tastes are what they were at seventeen.’ In our society, the telescoping of the generations is already happening: the knowledge, tastes, and social accomplishments of 13-year-olds are often the same as those of 28-year-olds. Adolescents are precociously adult; adults are permanently adolescent.”

“Vice is like suffering: each individual instance of it is regrettable, but what sensible person would wish to eliminate it altogether? Indeed, life without the possibility of vice, and therefore without its actual practice, would be deprived of all moral meaning.”

“ His house and farm might have been poor things, but they were his own.”

“The first requirement of civilisation is that men should be willing to repress their basest instincts and appetites: failure to do which makes them, on account of their intelligence, far worse than mere beasts.”

“THERE IS A PROGRESSION in the minds of men: first the unthinkable becomes thinkable, and then it becomes an orthodoxy whose truth seems so obvious that no one remembers that anyone ever thought differently. This is just what is happening with the idea of legalising drugs: it has reached the stage when with the idea of legalising drugs: it has reached the stage when millions of thinking men are agreed that allowing people to take whatever they like is the obvious, indeed only, solution to the social problems that arise from the consumption of drugs.

“It might be argued that the freedom to choose among a variety of intoxicating substances is a much more important freedom and that millions of people have derived innocent fun from taking stimulants and narcotics. But the consumption of drugs has the effect of reducing men’s freedom by circumscribing the range of their interests. It impairs their ability to pursue more important human aims, such as raising a family and fulfilling civic obligations. Very often it impairs their ability to pursue gainful employment and promotes parasitism. Moreover, far from being expanders of consciousness, most drugs severely limit it. One of the most striking characteristics of drug takers is their intense and tedious self-absorption; and their journeys into inner space are generally forays into inner vacuums.”

“Drug taking is a lazy man’s way of pursuing happiness and wisdom, and the shortcut turns out to be the deadest of dead ends. We lose remarkably little by not being permitted to take drugs.”

“Yet, enlightened as we believe ourselves to be, a golden age of contentment has not dawned—very far from it. Relations between the sexes are as fraught as ever they were. The sexual revolution has not yielded peace of mind but confusion, contradiction, and conflict. There is certainty about nothing except the rightness, inevitability, and irrevocability of the path we have gone down.

“In the modern view, unbridled personal freedom is the only good to be pursued; any obstacle to it is a problem to be overcome.”

“Having been issued the false prospectus of happiness through unlimited sex, modern man concludes, when he is not happy with his life, that his sex has not been unlimited enough. If welfare does not eliminate squalor, we need more welfare; if sex does not bring happiness, we need more sex.”

“The Dionysian has definitively triumphed over the Apollonian. No grace, no reticence, no measure, no dignity, no secrecy, no depth, no limitation of desire is accepted. Happiness and the good life are conceived as prolonged sensual ecstasy and nothing more. ”

“In my experience, devout Muslims expect and demand a freedom to criticise, often with perspicacity, the doctrines and customs of others, while demanding an exaggerated degree of respect and freedom from criticism for their own doctrines and customs. I recall, for example, staying with a Pakistani Muslim in East Africa, a very decent and devout man, who nevertheless spent several evenings with me deriding the absurdities of Christianity: the paradoxes of the Trinity, the impossibility of Resurrection, and so forth. Though no Christian myself, had I replied in kind, alluding to the pagan absurdities of the pilgrimage to Mecca, or to the gross, ignorant, and primitive superstitions of the Prophet with regard to jinn, I doubt that our friendship would have lasted long.”

Write a Comment